The Executive Sponsor’s Dilemma: Pacing at 87%

tldr; I am currently pacing around my basement in PA, watching a 96-hour manufacturing job enter its final, critical stages. But here is the terrifying part: I am not the architect.

It is Saturday morning. The house is quiet, except for the rhythmic, robotic hum of the Bambu Lab H2D printer in the basement.

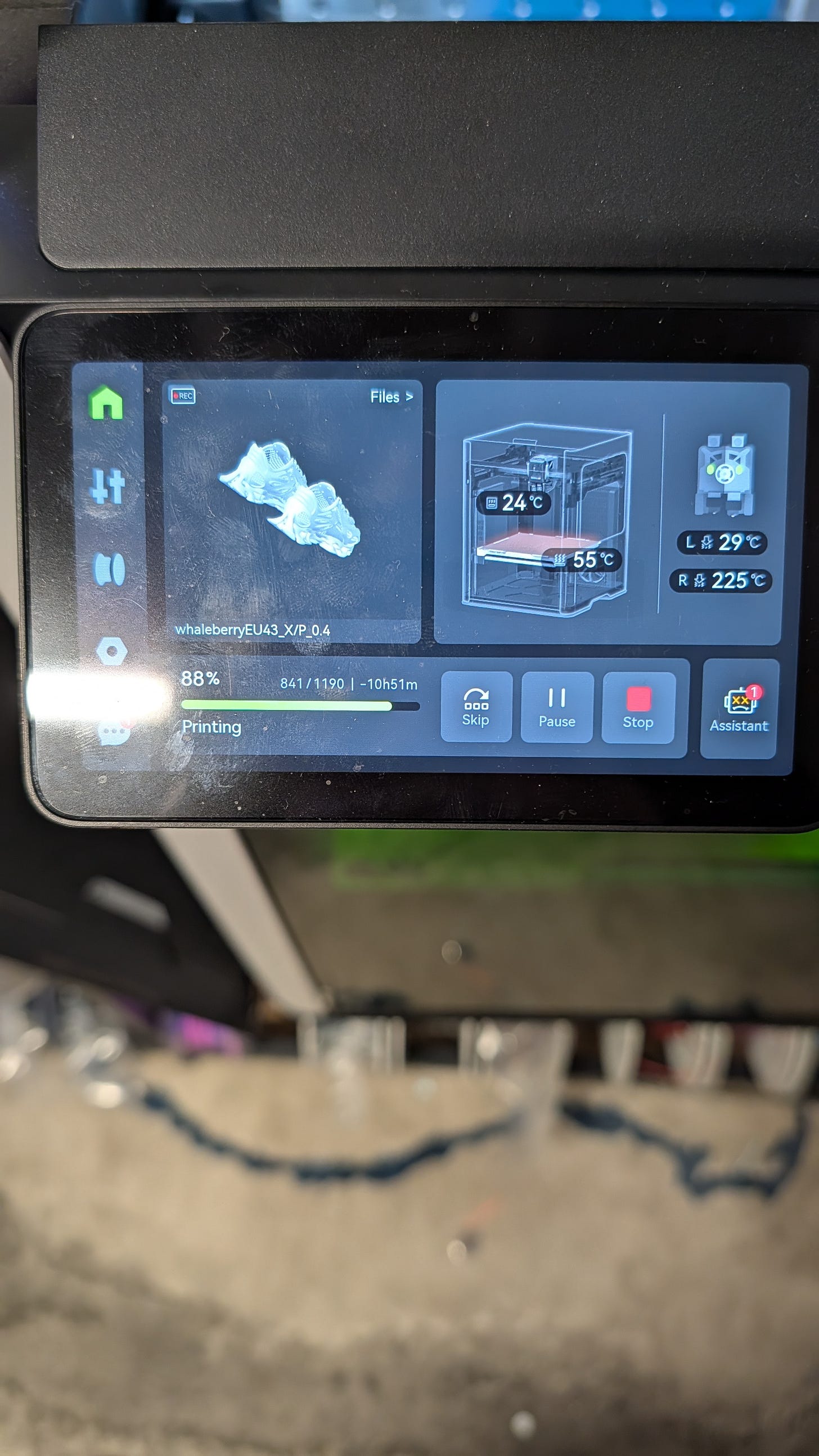

I should be relaxing. Instead, I am stress-eating pretzels and staring at a progress bar that currently reads 87%.

For the last 3.5 days, this machine has been depositing molten plastic to build a complex pair of "Whaleberry" shoes: a rigid white skeleton fused with a flexible "Frozen" blue skin.

If the print fails now—if a nozzle clogs, or the power flickers (happened last week), or a layer shifts by a single millimeter—I don't just lose $60 of filament or the 24 kWh of electricity I’ve pulled from the grid. I lose my son’s vision.

Because here is the raw truth I’m grappling with as I pace the floor: This isn't my project.

The Architect vs. The Sponsor

In my day job as a Director of HR Technology, I am usually the one designing the flow. I know the configurations. I know where the bodies are buried.

But in this basement? I am just the Executive Sponsor.

Justin (11) is the Architect.

He picked the model. He chose the "Frozen" TPU because it looked cool. He decided he needed custom 3D-printed footwear to wear to 6th grade. He has the Vision.

I just have the credit card and the anxiety.

As I watch the nozzle dart around the print bed, I realized this is exactly what it feels like for our business stakeholders during an enterprise implementation.

1. The "Visionary" Doesn't Care About Physics

Justin does not care about "layer adhesion" or "retraction settings." He doesn't care that TPU and PLA are chemically incompatible and require a mechanical dovetail joint to bond. He just wants the shoes to exist.

The Lesson:

This is your VP of HR. They don't care about the API limits or the data transformation map. They have a vision of the "Future of Work." As the Sponsor (me), my job isn't to burden the Architect (Justin) with the physics of why it might fail; my job is to sweat the details silently so his vision doesn't collapse under its own weight.

2. The Illusion of Control (The "Pacing Phase")

We are at hour 84 of 96.

If I touch the printer now, I ruin it. If I try to "optimize" the speed, I’ll cause a clog.

I have to trust the machine.

The Lesson:

This is the "Hyper-Care" freeze. As leaders, we want to do something during deployment. We want to send emails, check dashboards, and micromanage the queue. But the reality is, once you hit "Execute" on the cutover plan, you are no longer the driver. You are the passenger. You have to trust that the infrastructure you funded is robust enough to handle the load.

3. The "Mud" Reality (Go-Live)

This is the part that terrifies me most.

Let’s say this print finishes perfectly. I will peel off the supports, clean up the edges, and present these pristine, engineering marvels to the Architect.

Justin is going to put them on. And then?

He is going to run outside.

He is going to sprint through the snow in the backyard.

He is going to kick a soccer ball into the neighbor's fence.

I am treating these shoes like a museum piece. He is going to treat them like... shoes.

The Lesson:

We build our software in a "Clean Room." We test with perfect data. We assume users will read the Job Aid.

But the User (Justin) lives in the Mud.

The Clean Room: A user follows the script to request time off.

The Mud: A manager tries to approve a compensation change from their phone, with 10% battery, while waiting in line for coffee.

If the shoe falls apart because Justin ran through the mud, the shoe failed, not the boy.

If our system breaks because a manager didn't "follow the process," the system failed, not the user.

The Final Layer

The printer just chirped. We are at 88%.

The Architect is upstairs playing video games, blissfully unaware that his project is hovering on the brink of disaster.

The Executive Sponsor is down here, counting the kilowatt-hours and praying for adhesion.

But that’s the job. We absorb the anxiety so they can have the vision.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to go check the nozzle temperature one more time.

The other complexity of this is builders build for the clean room because clients too often either refuse to acknowledge the mud’s existence OR are completely unaware of the mud. They ask for shoes that work in the idealized world in their own head. BAs help with finding the mud, but are weirdly not empowered and if they talk about the mud get labeled negative. tl;dr design and delivery are hard, thanks for doing the work!